What Can Wheel of Fortune Tell Us About the Future of AI?

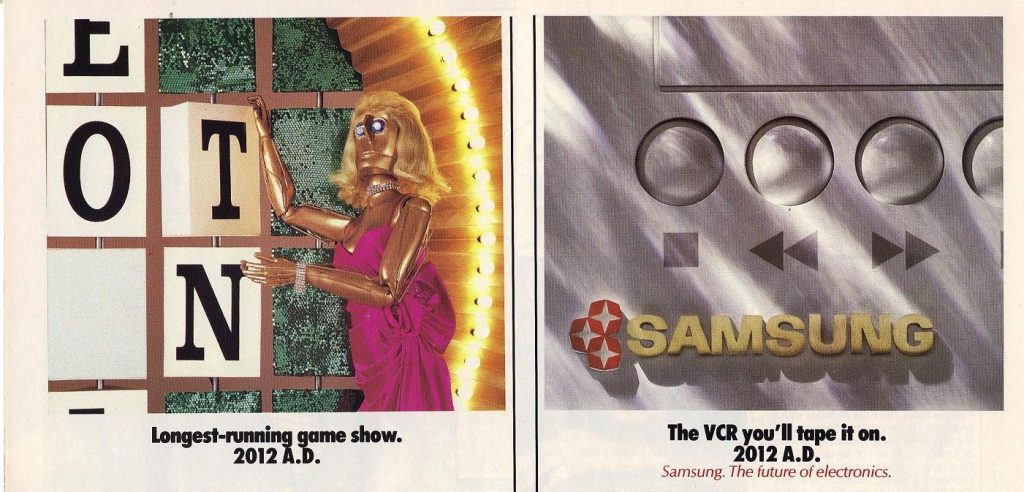

In 1988 Samsung ran a series of satirical advertisements in newspapers and magazines to promote the sale of video cassette recorders (VCRs). The ads predicting the future of broadcast media with a series of ridiculous ideas, like a trashy TV host becoming a candidate for US President or red meat being seen as health food.

One of the ads included an illustration of a game show featuring a robot in a blonde wig with the caption “Longest-running game show. 2012 A.D.”. At the time the most popular game show in the US was Wheel of Fortune, co-hosted Vana White, a glamorous blonde woman whose role involved turning squares on a large board to reveal letters so that contestants could guess the hidden words.

White was a very famous and recognisable individual and many people who saw the ad understood the image to be a reference to her. White sued Samsung alleging breaches of the US Federal Court under the California Civil Code 3344, California common law of privacy and breaches of federal competition laws. However the case was rejected in the first instance on the basis that the advertisement did not directly use White’s name or a direct representation of her image.

White appealed the judgement in the Federal Court in White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc., 971 F.2d 1395 (9th Cir. 1992) she was successful in her claim under the common law of privacy.

In his definitive 1960s study of the law of Privacy, William Prosser noted that the while most precedents had focused narrowly on the name and direct portrayal of images of individuals that the law had the potential to be more expansive.

“[i]t is not impossible that there might be appropriation of the plaintiff’s identity, as by impersonation, without the use of either his name or his likeness, and that this would be an invasion of his right of privacy.”

In White, the court noted that it was important that the courts have a flexible approach to the application of common law right of publicity based on the underlying legal principles, not by simply applying the law in accordance with the specific circumstances of prior cases.

A rule which says that the right of publicity can be infringed only through the use of nine different methods of appropriating identity merely challenges the clever advertising strategist to come up with the tenth.

The court’s observation about the innovative nature of the advertising industry could easily be applied to the AI industry today and has the potential to cause significant issues for AI companies as they defend legal actions that allege the widespread use and exploitation of personality rights by their services.

Rights of publicity had already been expanded by the courts in Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc. where a service provider had been found to infringe the publicity rights of late night host Johnny Carson by using his signature show introduction “Here’s Johnny” in relation to their portable convenience operations.

In considering the White case, the court pointed to the decision in Carson where it was found that “If the celebrity’s identity is commercially exploited, there has been an invasion of his right whether or not his “name or likeness” is used.”

In upholding White’s claim, the court made powerful argument that the right of publicity is one that should be read broadly and applied based on the specific circumstances of each case.

The precedent in White should be seen as a warning to AI deepfake services and those that seek to exploit the publicity rights of prominent individuals without approval. While AI image generators, video creators, LLMs and voice emulators may have made it easier than ever to create credible deepfake versions of famous individuals, the rights to exploit such deepfakes clearly continues to reside in those individuals (or their estates).

While most recent AI lawsuits are based on Copyright infringement claims, a number of cases have asked the courts to examine the issue of publicity – such as the lawsuit brought by the estate of George Carlin,. Carlin’s estate sued the podcast Dudesy for publishing an AI generated deepfake comedy set using the voice and likeness of Carlin, called “George Carlin: I’m Glad I’m Dead”.

The Carlin case was settled out of court – depriving the both the tech industry and lawyers of much needed guidance on this issue. It does seem likely that in the same way that AI services continue to proliferate that legal disputes over personality rights will likewise continue to pile up.